It was the end of a wonderful spring, these two months of May and June 1940. After the harshness of a exceptionaly cold winter, flowers were revigorating under the soft warmth that announced a beautiful summer. Despite the international tensions and the situation of War, France was living happy days, trusting its strength and it’s army, “the best in the world” according to its leaders and many foreign observers.

War... The Great War’s nightmare was still haunting the memories and the fireplace stories of fathers, uncles, friends and cousins, many of whom were “broken jaws” as were called the disfigured casualties. The old “Poor Front Dudes” as they called themselves, as well as the too many families of the lost, carried in themselves the hatred mixed with terror of the trenches, the gas, the bloody bayonet assaults under heavy artillery and the long years of cold, mud and death of the 1st World War.

The French had figured it out. War had shown its true face to the “world’s best infantrymen” as the frenchmen soldiers were dubbed, all enlightened with napoleonic glory and full of vengeance against the Prussian, the “Boche” (French nickname for the Germans, as Fritz or Krauts in English). War had shown its most simple and cruel side. Covered with blood and mud, uniforms had no more prestige and the flowers on the rifles had long faded away. The heroic assaults weren’t any more than mass massacres without any strategic or even tactical advantages. Thousands of men were killed or badly wounded to regain control of a stronghold or to advance a few hundred yards, only to fall back to original positions. Glory, like heroism, are words that are strangely missing of the era’s military language. No more glory, no more heros or military values: all was melted down in an awful mix of mud, blood, putrefaction, tears and death. Strategy or means wouldn’t make the difference, it would be the army who died slower than the other!

The French, without really wining it, managed not to loose the war and despite the politician arrogance of the Versailles peace treaty and the victory parade on the Champs-Elysées, all the “hairies”, as the trench soldiers called themselves, swore it strongly: this will be the last war, the last of the last! No one wants to make war anymore in France. Everyone just wants to live and enjoy loved ones peaceably instead of dying at Verdun or at the Côte 304.

The interwar period still isn’t a time without problems, peaceful and full of hope. France is badly hurt. Its economy, centered on the war effort, is aching from the disaster. The North Eastern part of France is shattered and no more cultivable because of the millions of unexploded shells and ammunition. 1.5 million frenchmen between 18 and 55 years old are dead and twice more are wounded, gased, crippled or shocked. The euphoria of victory doesn’t last long, so important is the damage and so huge is the reconstruction work. The world economy is stumbling as well and the 1929 stock market krach plunges even more the world into a climate of insecurity and lack of confidence in the future that favors the uprising of extreme-right leaders, ultranationalists and demagogic who gather large numbers of voters in peoples frightened by a unstable world. Before 1929, Italy falls for a fascist government (1922) with a program of national pride, italian glory and economic, cultural and even architectural revival . This “fascist” movement then reaches Germany (1933) and Spain (1936), always tainted with exacerbated and bellicist militarism.

The serious events start in 1932 when Japan assaults China by invading and annexating Manchuria. It is the beginning of the expansionist movements of empires starving for power and conquest. Germany in Europe and Italy in Africa lauch military or diplomatic conquests, under the more and more concerned eye of the other nations. But the directly concerned powers, France and Great-Britain, rocked with internal problems, don’t move. Their unstable and feverish governments can only undergo the totalitarian law of the Italo-Germans. Abyssinia (now Ethiopia) is conquered under the eyes of British Egypt and French Equatorial Africa, while Germany, breaking the Versailles Treaty, successively grabs Saarland, Rhineland, Austria, Czechoslovakia and Poland. It is only this latter agression that pushes the Allies out of their numbness. On August 28, 1939, reservists are mobilized and on September 3, after the declaration of war, the whole conscription classes are mobilized.

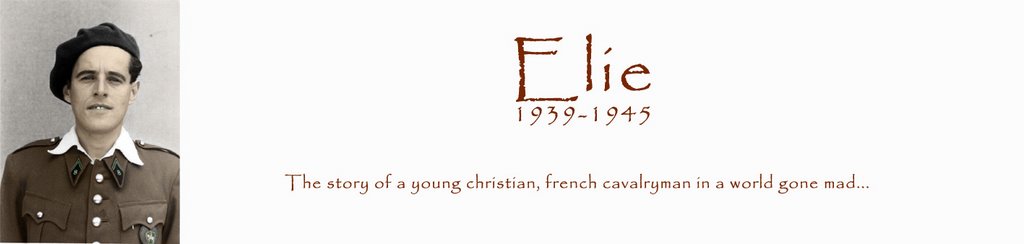

Among the August 28 reservists, a 24 year-old young man, recently engaged, Elie Garzaro, sergeant in the 8th “Chasseurs” Horse Regiment. He is appointed to the 71st Infantry Division Reconnaissance Group (71st IDRG) under the command of Major Massacrier. He leaves his Gironde birthplace, his law studies, his parents and his fiancée to join the troops massed in the Lorraine hills behind the Maginot Line. He will come back on leave, to marry his love, and then during the winter, but in the spring 1940, that beautiful spring and its soft warmth awakening colourful flowers, he is captured under the rainfall of iron and fire of the german Blitzkrieg. He then disappears for five long years in the German Stalags, casualty of a war lost before it began in which France looses, along with its dominant world power, its honor of country of Liberty. It will fall down in hypocrisy, shame and collaboration and the struggle between its children will be as bloody as terrible.

What would have happened if France had found the courage and strength to overcome Hitler’s hordes? What would have become of the world if France had victoriously resisted Nazi Germany? The answers are only speculations that fill the minds of the million and half young frenchmen who march in long columns of prisonners towards Germany.

Saddenend by the defeat and its consequences, harassed by thirst and the miles, his forehead soaked with sweat, his kepi under his arm, Sergeant Garzaro thinks about everything he leaves behind and all that awaits him. He now only has his faith and hope and it is thanks to them that he will hold. Five years of deprivation, uncomfort, had treatment and decieved hopes a thousand miles from home. Still, his faith is steady and his hope strong. In a world gone mad, a young christian french soldier was surviving, hoping and believing. An example ton consider.

This site is dedicated to his short story, from 1939 to 1945, that he didn’t tell much and that no one will really know.